Introduction

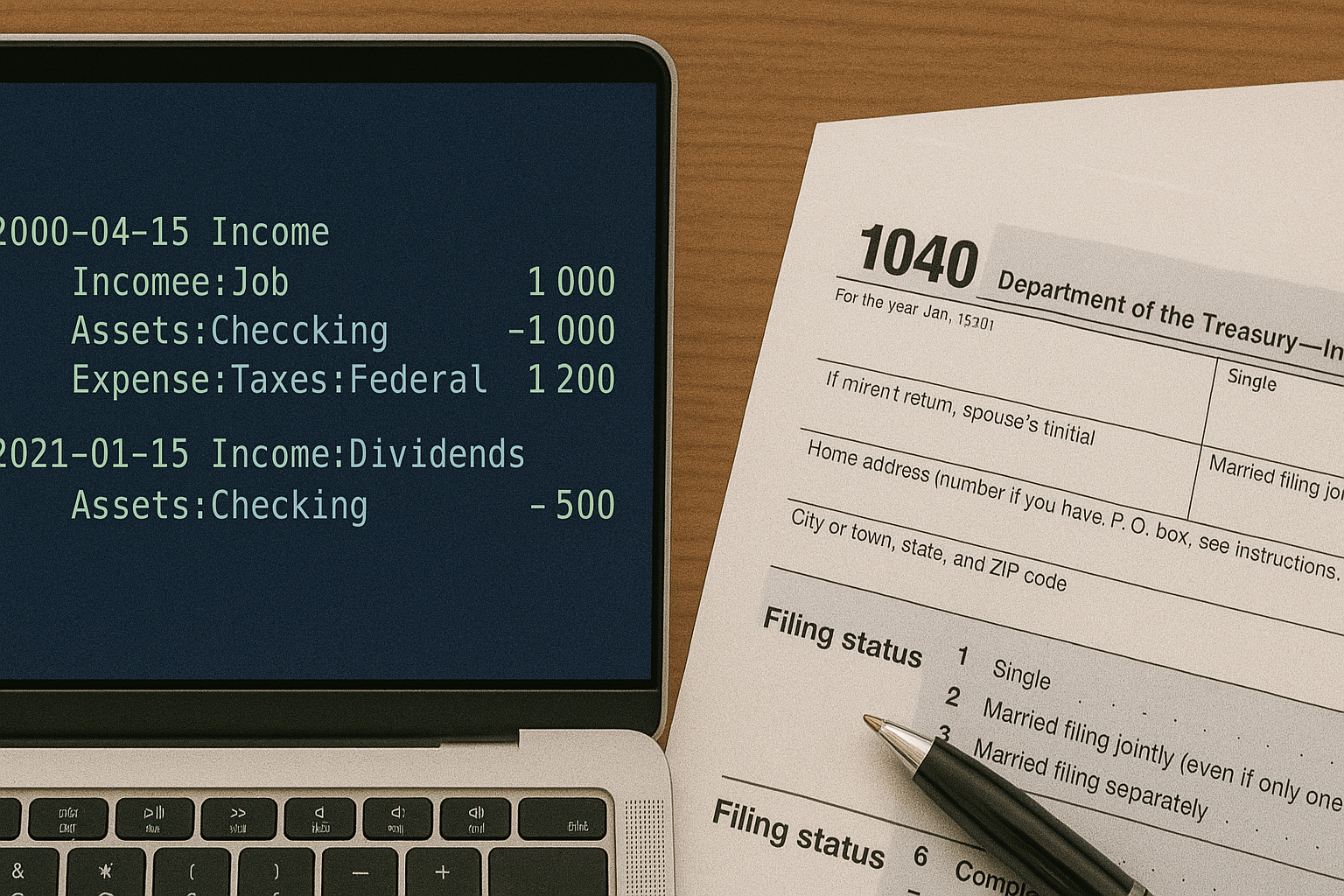

Tax accounting is one of the most crucial aspects of personal and business bookkeeping, yet it can be intimidating for newcomers to double-entry accounting systems like Beancount. This guide will walk you through the fundamental concepts and practical techniques for accurately recording various types of taxes in your Beancount ledger.

The Beancount example in this post can be found in: https://github.com/flyaway1217/beancount_example/blob/main/single_examples/taxes.bean

Tax Categories

Before diving into specific examples, it’s important to understand how taxes fit into your daily life. Taxes generally fall into several categories:

- Income Taxes: Federal, state, and local income taxes that you owe or have paid.

- Payroll Taxes: Social Security, Medicare, unemployment insurance, and other employment-related taxes

- Sales and Use Taxes: Taxes paid on purchases.

- Capital gain Taxes: This is usually reflected in the annual tax return

forms. There is no need to set up a specific

Expensesaccount for capital gain taxes. - Property Taxes: Real estate and personal property taxes.

Setting Up Your Tax Account Structure

A well-organized account hierarchy is essential for tax tracking.

Each tax category has its own branch in the Expenses hierarchy except the property taxes.

I put the property taxes under the Expenses accounts of the corresponding real

estate, which makes more senses to me.

The Expenses account hierarchy I recommend is as following:

2024-01-01 open Expenses:Taxes:Federal:IncomeTax:Withhold

2024-01-01 open Expenses:Taxes:Federal:IncomeTax:Payments

2024-01-01 open Expenses:Taxes:Federal:IncomeTax:Refund

; Social Security

2024-01-01 open Expenses:Taxes:Federal:SocialSecurityTax

; Medical Care

2024-01-01 open Expenses:Taxes:Federal:MedicareTax

; Sale Tax

2024-01-01 open Expenses:Taxes:SaleTax

Following the Computing Taxes with Beancount , I split the federal income taxes further into three subaccounts:

Withhold: This account records the amount withheld by the government throughout the year. Note that this does not reflect your total federal income tax liability.Payments: This account captures any additional tax payments made when filing your tax return, typically in the second year, if you owed more than what was withheld.Refund: This account records any tax refunds received, if applicable, when the total withheld and paid exceeds your actual tax liability.

The sum of the above three accounts is your total federal income tax expenses,

which reflects in the Expenses:Taxes:FederalIncomeTax. This setup provides a

clear breakdown of how your federal income tax is composed.

Recording Taxes Based on Paychecks

When you receive your paychecks, it usually states

- The amount withheld for taxes

- The total pre-tax deductions

- The total post-tax deductions

- Contributions to pre-tax accounts

- Contributions to post-tax accounts

- The net pay

Translating a paycheck into your Beancount ledger involves many considerations. For simplicity, this post focuses solely on the tax-related aspects of a paycheck. A comprehensive guide to mapping an entire paycheck into Beancount will be covered in a dedicated blog post.

Now, let us assume an example paycheck looks like:

|

|

To convert this simplified paycheck into a Beancount transaction:

2025-07-15 * "Employer" "Salary"

; Gross income

Income:Work:Salary -6,000 USD

; Tax

Expenses:Taxes:Federal:IncomeTax:Withhold 1,200.00 USD

Expenses:Taxes:Federal:SocialSecurityTax 372.00 USD

Expenses:Taxes:Federal:MedicareTax 87.00 USD

; Direct deposit

Assets:Cash:Checking:Chase 4,341.00 USD

Handling Tax Returns

One challenge in recording tax expenses is that we can’t finalize them until we file our tax returns, which typically occurs in the following year. If we record additional tax payments or refunds in the year they’re received, it can misrepresent the previous year’s tax expenses when we later analyze them.

Let us use a specific example to demonstrate the issue and solutions.

Tax Return Examples

Suppose in 2024, your total income amounts to 100,000 dollars. Your employer withholds 10,000 dollars for federal income taxes. Upon filing your tax return in April 2025, your CPA determines a total tax liability of 13,000 dollars for 2024, leading you to pay an additional 3,000 dollars.

To log the salary and the withheld taxes for 2024, you can consolidate them into a single transaction dated December 1, 2024:

2024-12-01 * "Employer" "Salary"

; Gross income

Income:Work:Salary -100,000.00 USD

; Tax

Expenses:Taxes:Federal:IncomeTax:Withhold 10,000.00 USD

; Direct deposit

Assets:Cash:Checking:Chase 90,000.00 USD

This transaction reflects the gross income, the amount withheld for taxes, and the net salary deposited into your checking account.

Next, we need to record the extra tax payment. A naive way of doing it is:

2025-04-15 * "IRS" "Tax payments for 2024"

Expenses:Taxes:Federal:IncomeTax:Payments 3,000.00 USD

Assets:Cash:Checking:Chase -3,000.00 USD

However, this approach inaccurately attributes the expense to 2025, whereas it pertains to the 2024 tax year. This misclassification can lead to discrepancies when analyzing expenses for 2024.

Option 1: Dedicated Subaccounts for each Year

One method to accurately attribute the expense to 2024 is by creating dedicated subaccounts for that tax year:

2024-01-01 open Expenses:Taxes:FederalIncomeTax:2024:Withhold

2024-01-01 open Expenses:Taxes:FederalIncomeTax:2024:Payments

2024-01-01 open Expenses:Taxes:FederalIncomeTax:2024:Refund

Then, we can rewrite the extra tax payments as:

2025-04-15 * "IRS" "Tax payments for 2024"

Expenses:Taxes:Federal:IncomeTax:2024:Payments 3,000.00 USD

Assets:Cash:Checking:Chase -3,000.00 USD

In this way, the account Expenses:Taxes:FederalIncomeTax:2024 summarizes the

total tax expenses for 2024.

Option 2: Use Two Separate Transactions

However, Option 1 is not the optimal solution. Although it correctly logs the total tax expenses for the 2024, it fails to correctly represent the total expenses for the 2024. If we want to query for the total expenses for 2024, we are still in short of the 3000 because that expenses is still logged in 2025.

The underlying issue here is that Beancount requires all postings in a transaction to share the same date, but in our case, the extra tax payment or refund occurs in the following year, while the expense pertains to the previous year. The postings in the same transaction happens in different dates.

So, following this thought, we can split the tax payment into two different transactions:

2024-12-31 * "IRS" "Tax payments for 2024"

Expenses:Taxes:Federal:IncomeTax:2024:Payments 3,000.00 USD

Liabilities:Hold:Expenses:Taxes:Federal:IncomeTax:Payments -3,000.00 USD

2025-04-15 * "IRS" "Tax payments for 2024"

Liabilities:Hold:Expenses:Taxes:Federal:IncomeTax:Payments 3,000.00 USD

Assets:Cash:Checking:Chase -3,000.00 USD

The first transaction records the tax expense on 2024‑12‑31, using a

Liabilities account to balance the entry. No cash actually changes hands

yet—this transaction simply reflects the tax liability incurred in 2024. Then,

when you file your taxes in 2025, you make the payment and zero out the

liability by paying off the Liabilities account to record the real cash

outflow.

This two-steps method ensures that:

- The tax expense is correctly captured in 2024, and

- The cash movement is reflected in 2025.

All that’s required is an additional Liabilities account to hold the obligation in between.

This same approach can be applied whenever an expense and its cash settlement occur in different fiscal periods.

Plugin to Automate

Although manually applying this accrual accounting technique works, it can become tedious to remember all the details. Fortunately, the effective_date plugin automates exactly this process.

What the plugin does:

- Lets you assign different dates to individual postings within a single transaction.

- Automatically splits the entry at load-time, using a virtual holding account to bridge the period between the expense and the payment dates.

- Ensures that the expense is recorded in the correct fiscal year, while the cash outflow is logged when it actually occurs.

For our example, we can write the transaction as:

2025-04-15 * "IRS" "Tax payments for 2024"

Expenses:Taxes:Federal:IncomeTax:Payments 3,000.00 USD

effective_date: 2024-12-31

Assets:Cash:Checking:Chase -3,000.00 USD

When processed, the plugin creates two logical postings:

- Expense logged as of 2024‑12‑31 in the proper year.

- Cash reduction recorded when the payment happens in 2025‑04‑15 using a holding account under the hood.

This keeps your records accurate and consistent across fiscal periods—without requiring manual juggling of multiple transactions or extra liability accounts.

The details of how the Beancount plugin works are beyond the scope of this post. We’ll explain how to configure and use the plugin in a separate blog post focused on the Beancount plugin mechanism.

Recording Sales Tax on Purchases

When you’re buying something that’s subject to sales tax, it’s simple to include the tax in the total purchase price:

2025-07-19 * "AMAZON" "buy grocery"

Expenses:Daily:Grocery 12.32 USD

Expenses:Taxes:SaleTax 1.28 USD

Assets:Cash:Checking:Chase -13.60 USD

Conclusion

Recording taxes accurately in Beancount requires understanding both tax concepts and double-entry bookkeeping principles. By establishing a clear account structure, maintaining consistent recording practices, and leveraging Beancount’s reporting capabilities, you can create a comprehensive tax tracking system that will serve you well during tax season and beyond.

Remember that while Beancount is an excellent tool for organizing your financial data, it’s always wise to consult with a qualified tax professional for complex tax situations or when in doubt about proper tax treatment of specific transactions.

The investment in time to properly set up and maintain your tax accounts in Beancount will pay dividends in reduced stress, better financial visibility, and more efficient tax preparation processes.